Unlike in the Cold War, the United States faces the prospect in the next decade of two peer nuclear adversaries, which will together have twice as many strategic nuclear weapons as it does. According to a senior American official visiting Australia last month, by 2034 China will have as many strategic nuclear weapons as the US does today. So, a decade from now America may be outnumbered by Russia and China combined having over 3,000 strategic nuclear warheads to America’s 1500.

Under the terms of the 2018 New START Treaty, Russia and America are each allowed 1550 strategic nuclear warheads and 700 deployed intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched ballistic missiles and heavy nuclear bombers. This treaty expires on 5 February 2026. But Russia last year ‘suspended’ its treaty commitments—though it claims it will abide by the numerical limit of 1550 deployed nuclear warheads.

The United States and Russia have successfully negotiated strategic nuclear arms reduction talks from the early 1970s until now. At the height of the Cold War, the US nuclear arsenal numbered more than 32,000 weapons and the Soviet arsenal more than 45,000. The two have also withdrawn about 14,000 tactical nuclear weapons from forward deployments in places such as Europe. But the question now arises whether that era of careful, considered—and verifiable—cuts to strategic nuclear capabilities is over.

The Russians and the Americans are no longer talking at the political level about these vital issues, although expert talks do continue. And several previous bilateral arms control treaties have been cancelled, including the Antiballistic Missile Treaty, the Theatre Nuclear Forces in Europe Treaty, the Open Skies Agreement, the Conventional Forces in Europe Agreement and others.

On 7 June, according to Pranay Vaddi—the special assistant to the president for arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation at the National Security Council—Russia, China and North Korea ‘are all expanding and diversifying their nuclear arsenals at a breakneck speed and showing no interest in arms control.’ Vaddi observed that the last decade has revealed serious cracks in the international pillars of reducing nuclear dangers, the salience of nuclear weapons, and limiting strategic arsenals of the largest nuclear powers.

When I was last in Moscow, in 2016, a senior military officer at the colonel general level stressed that tense bilateral relations were all leading to a nuclear miscalculation. Regular meetings and negotiations over intricate technical details were a thing of the past. Since then, bilateral relations between Russia and America have deteriorated further. President Vladimir Putin at least wants us to think he is seriously toying with the idea of using nuclear weapons. Who knows what goes on in his obsessive mind? But Putin needs to remember that at the height of the Cold War, the Pentagon’s calculations were that, in the event of a full-scale nuclear strike on Russia, America would kill about one quarter of Russia’s population, or 70 million people, in the first 48 hours.

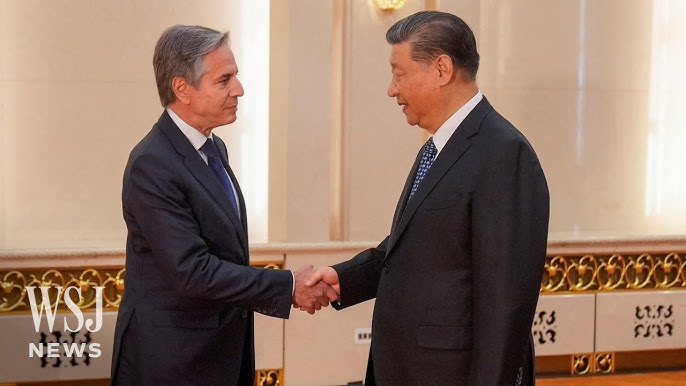

China has absolutely refused to be involved with the Americans about nuclear arms control and verification. It claims that its strategic nuclear forces are so modest compared with those of the US that there is no point in any talk about negotiations. It is true that until recently China’s strategic nuclear stockpile has not been much more than that of either Britain or France (200 to 300 nuclear weapons each). However, according to the Pentagon, China now has about 500 nuclear weapons and will reach 1000 by 2030. In this context, I have been advised that the US is already adding to its nuclear military targets in China.

There can be no doubt that the type of limits that the US might be able to agree with Russia would be affected by the size and scale of China’s nuclear buildup and the United States’ deterrence needs in relation to Beijing.

My impression is, however, that as yet there is no plan in the US to equal the combined numbers of nuclear weapons of Russia and China. This would be a hugely expensive step and would likely take a couple of decades. Although warheads could be taken out of reserve stockpiles, finding extra delivery vehicles is quite a different proposition.

The national security adviser to the president has made it clear that America ‘does not need to increase its nuclear forces to match or outnumber the combined total of our competitors to successfully deter them.’

Even so, it would seem obvious that 1500 nuclear weapons will be insufficient if the US is to have the capacity to wage major nuclear war simultaneously on both China and Russia. Vaddi made it quite clear that the US ‘will need to continue to adjust our posture and capabilities to ensure our ability to deter and meet other objectives going forward.’ The special assistant also said the president had ‘recently issued updated nuclear weapons employment guidance, which takes into account the realities of a new nuclear era.’ This updated nuclear guidance emphasises ‘the need to account for the growth and diversity of the PRC’s nuclear arsenal—and the need to deter Russia, the PRC, and North Korea simultaneously.’ Moreover, absent a change in the growth trajectory of adversary arsenals—for which, read those of Russia and China—the US may reach a point in the coming years ‘where an increase from current deployed numbers is required.’

In brief, Russia and China are forcing the US and US allies to prepare for a world where nuclear competition occurs without guarantees of numerical constraints.

There are several ways in which America might remodel its nuclear posture. At present, the US is developing a new ICBM type, the LGM-35 Sentinel, to replace the 450 old Minuteman ICBMs and serve from 2029 to 2075, although the program is running more than two years late. The initial costs of this project have rapidly risen from an initial budget of US$95.3 billion to more than US$125 billion in January 2024 and a revised defence contract estimate of US$141billion in July 2024. According to the secretary of the air force, the Sentinel program has now encountered ‘unknown unknowns’.

I understand that the nuclear weapons load of the Ohio class SSBN can be quickly made significantly bigger if the New START Treaty is not extended in February 2026. In addition, more of the hard-to-detect Northrop Grumman B-21 bombers can be built. However, Russia itself is also going through significant nuclear modernisation, including developing the Sarmat ICBM that will replace the Cold War SS-18 Satan, which carried a single 20-megaton warhead or 10 one-megaton independently targetable warheads. Russia is also developing a new ballistic-missile nuclear submarine (SSBN) as well as a very large nuclear-armed torpedo.

However, it is important here to understand that both China’s and Russia’s so-called survivable second-strike nuclear capability in their SSBNs are highly vulnerable to pre-emptive destruction by the United States’ decisive superiority in underwater warfare. China appears to know that its SSBNs are very vulnerable and is investing heavily in missiles on trucks to complicate US targeting.

Another route to expansion that the US may be contemplating is to use some of its huge holdings of reserve nuclear warheads, which total 4200. According to the 2009 report of the Commission on America’s Strategic Posture, the US retains a large stockpile of reserve weapons ‘as a hedge against surprise, whether of a geopolitical or a technical kind.’

The geopolitical surprise could mean, for example, a sudden change in leadership intent in Russia or China that could pose a threat to the United States, which might drive the US to reload reserve nuclear weapons on available delivery systems. To hedge against technical surprise—such as, perhaps, an opponent’s deployment of ballistic missile defence—the US currently retains two warhead types for each major delivery system. This approach to hedging requires holding a significant number of non-deployed nuclear warheads.

All this suggests that—if America’s strategic circumstances should dramatically worsen or if a highly challenging technological breakthrough had been achieved by one of its nuclear adversaries—Washington could quickly access around 4000 reserve strategic nuclear warheads. The commission noted that the US maintains ‘an unneeded degree of secrecy’ about the number of nuclear weapons in its arsenal, including not just deployed weapons but also weapons in the inactive stockpile and those awaiting dismantlement.

This is also where extended nuclear deterrence comes in. Washington will need to take careful notice of how countries such as Japan will react if it loses its capacity to reassure Tokyo that extended nuclear deterrence will still work. Japan faces potential nuclear threat not only from China and Russia but also from North Korea (whose relatively crude nuclear capability should not be underestimated). Extended deterrence is not, however, a foregone conclusion—not least for America’s allies.

This concept was relatively straightforward in the Cold War because it involved deterring only one nuclear superpower, the Soviet Union. Needless to say, it was never tested in practice as far as Australia was concerned even though we were an important Soviet target with regard to the joint US–Australian facilities at Pine Gap, Nurrungar and North-West Cape. The concept of extended nuclear deterrence remains a theory: it depends on the perceptions by the adversary of America’s nuclear intent to dissuade it from using nuclear force against the US or a US ally. Allies face ever-increasing nuclear and conventional threats from Russia, China and North Korea and may become increasingly worried about the credibility of US guarantees.

In the Cold War, the deterrence calculus was relatively simple. The president authorised guidance to hold a broad array of targets at risk and also authorised the nuclear operational plans for doing so. The deterrent effect was understood to derive from the nuclear damage that an adversary might calculate and its uncertainty as to whether it could bear the cost—or even predict it reliably. The US went to great lengths in the Cold War to ensure that its deterrent was perceived as credible and effective, including through strong declaratory policies that in the event would have made it very difficult for it to back away from its nuclear deterrent commitments.

It is important to understand that deterrence is in the eye of the beholder. Whether potential adversaries are deterred (and US allies are assured) is a function of their understanding of US capabilities and intentions. This implies that the US needs a spectrum of employment options for nuclear and precise conventional forces, along with the requirement for forces that are sufficiently lethal and certain of their result to put at risk an appropriate array of the adversary’s nuclear capabilities credibly.

Whereas during the Cold War the USSR understood all too well that the consequences of nuclear war with the US would have been devastating for Russia, it is not as clear as it needs to be that contemporary China has drawn the same conclusion—despite the fact that the sheer size and density of China’s population makes it especially vulnerable to all-out nuclear war.

This underscores the potential challenges of effective deterrence, as it brings with it more openings for ignorance, motivations, distorted communications and a lack of understanding. Essential to the future effective function of nuclear deterrence is that the US and its allies gain insights into the strategic thinking of the nations being deterred and, so, how best to communicate with them in a crisis.

While extended nuclear assurance and persuasion have been important factors in the US for a long time, there does not appear to be any widely accepted methodology for reaching a decision on how many weapons are needed for these purposes.

As an important first step, the US should consult more closely with its allies regarding their views of what is required for their assurance. This is an issue where Australia should have a much more extensive dialogue with its other key strategic partners in the Asia-Pacific region, especially Japan.

Australia must now pay urgent attention to this important new threat of the US deterring two peer nuclear powers, perhaps simultaneously. Canberra should reverse the decline of resources of the intelligence community devoted to foreign nuclear weapons capabilities, programs and intentions. This subject has not attracted high-level attention since the end of the Cold War more than 30 years ago.

The Australian defence organisation has no collective memory of how we dealt with this issue from the early 1970s until the collapse of the USSR in 1991. Our hosting of Pine Gap and Nurrungar during that time gave us highly privileged access to US thinking about nuclear war and nuclear deterrence. The Australian defence organisation needs to revisit this critical policy issue now.