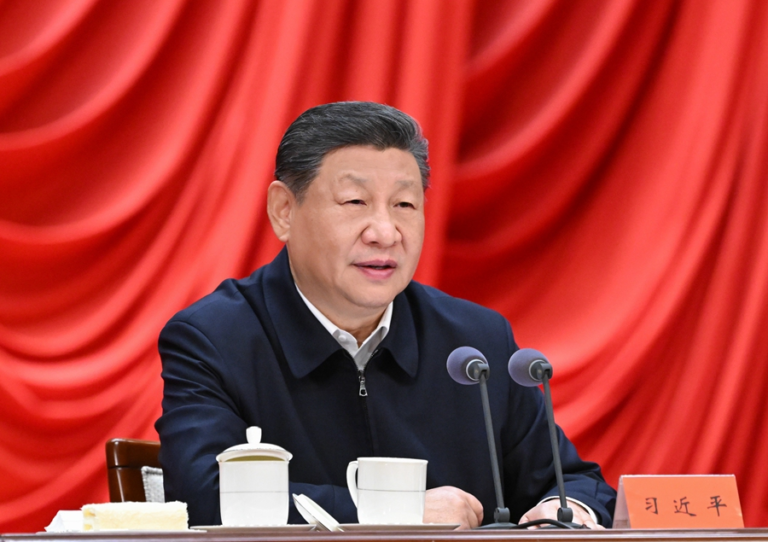

China reportedly agreed in July 2025 to sign a Southeast Asian treaty banning nuclear weapons in the region.

The Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone (SEANWFZ) treaty was signed in 1995 by the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and entered into force in 1997. Signatories agree not to use or move nuclear weapons in the region, including in territories, exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and continental shelves.

The treaty includes a protocol for the five key nuclear weapon states (NWS) — China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States — to sign in support of limiting the use of nuclear power by ASEAN members to peaceful purposes, such as energy production. Over the past 30 years, none of the five recognized NWS signed the protocol largely due to concerns over mutual security guarantees and freedom of navigation.

Analysts say China’s recent pledge to sign the protocol has little to do with limiting nuclear proliferation. Instead, it is a strategic move to increase Beijing’s leverage over Southeast Asian states and self-governed Taiwan, and to weaken U.S. ties to the region.

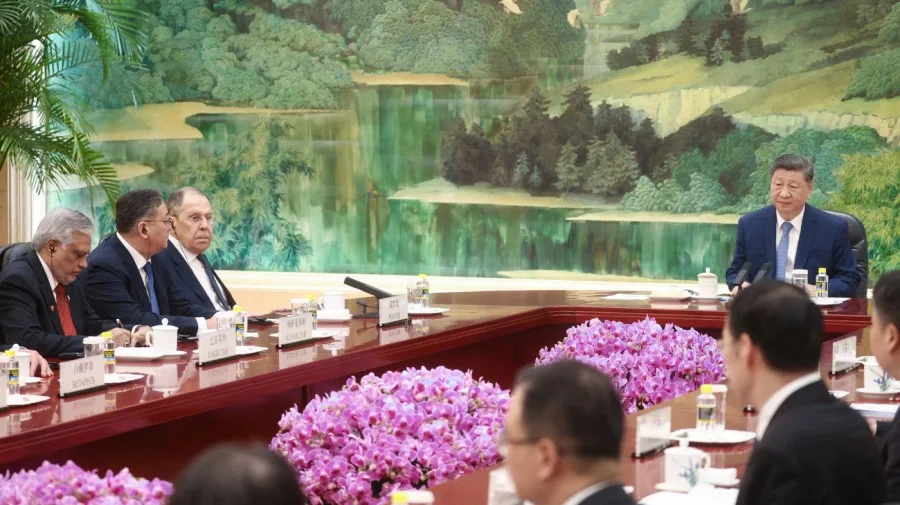

Russia has also agreed to sign the treaty, according to Malaysian Foreign Minister Dato’ Seri Mohamad Hasan, the Reuters news agency reported. The U.S. is reviewing the issue, according to reports.

Mohamad Hasan said China agreed to sign the treaty as soon as the documents can be prepared, Reuters reported. China has expressed interest in signing the treaty since 1999 and now is offering to “lead” the effort to establish the zone and persuade other NWS to join the treaty.

Philippine Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro Jr. dismissed China’s offer as meaningless without transparency and a disarmament commitment. He called for China to first denuclearize or open itself to inspection by the United Nations International Atomic Energy Agency and other multinational inspectors, according to Philippines-based GMA News Online.

Depending on how the treaty is interpreted, its implementation could weaken the U.S. nuclear umbrella on which countries such as the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand depend for deterrence and render them more susceptible to Chinese influence, analysts say. For example, the treaty could be used to restrict U.S. military access to ports and airspace in the region if nations interpret its provisions to pertain to nuclear-capable platforms.

“The expansive geographic coverage of SEANWFZ — if implemented — would undercut the deployment of foreign powers’ nuclear assets in a large swathe of the maritime area in China’s vicinity, which would enhance China’s strategic security,” Hoang Thi Ha, a senior fellow and co-coordinator of the Regional Strategic and Political Studies Programme at ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, wrote in 2023.

Moreover, China could use the treaty to delegitimize “the military presence of foreign powers in the region, thereby contributing to the Chinese anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) strategy in normative terms.”

Beijing could use ambiguities in the treaty to challenge freedom of navigation operations by the U.S. and its Allies and Partners in the South China Sea, increasing China’s ability to coerce nations with rival claims in the vital trade route.

In a more specific way than entailed in the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, the SEANWFZ treaty covers EEZs and continental shelves in the resource-rich sea, many of which are subject to territorial and maritime disputes among China and Southeast Asian nations. Analysts contend that China could use its claims to define the geographical scope of SEANWFZ and selectively apply it to suit Beijing’s interests and manipulate the outcome of its disputes.

“For example, China may challenge nuclear deployments of other NWSs in the zone as violations of SEANWFZ but it can justify the presence of its nuclear assets in the zone on the grounds that such deployment takes place within China’s (claimed) territory and jurisdiction,” Hoang wrote.

China’s maneuvers also could pressure the 10-member ASEAN not to cooperate with the U.S. under the guise of treaty compliance, analysts said.

China also may be motivated to sign the treaty to make it appear as if the Chinese Communist Party is a responsible nuclear actor in the region.

In fact, China is rapidly increasing its nuclear reach, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), which estimates that China has at least 600 nuclear warheads. In recent years, China’s nuclear arsenal has grown faster than that of any other country, adding about 100 warheads a year.

“By January 2025, China had completed or was close to completing around 350 new ICBM [intercontinental ballistic missile] silos in three large desert fields in the north of the country and three mountainous areas in the east,” SIPRI reported in June 2025. “Depending on how it decides to structure its forces, China could potentially have at least as many ICBMs as either Russia or the [U.S.] by the turn of the decade.”

Although SEANWFZ doesn’t cover Taiwan, the treaty could limit the ability of the U.S. and its Allies and Partners to support the defense of the island, which China claims as its territory and threatens to annex by force. Such limitations would make a blockade or invasion of Taiwan less costly for China, analysts said.

Given that the treaty does not restrict China’s nuclear arsenal, Beijing only gains by signing the protocol. The treaty does little to advance nuclear disarmament, analysts note.