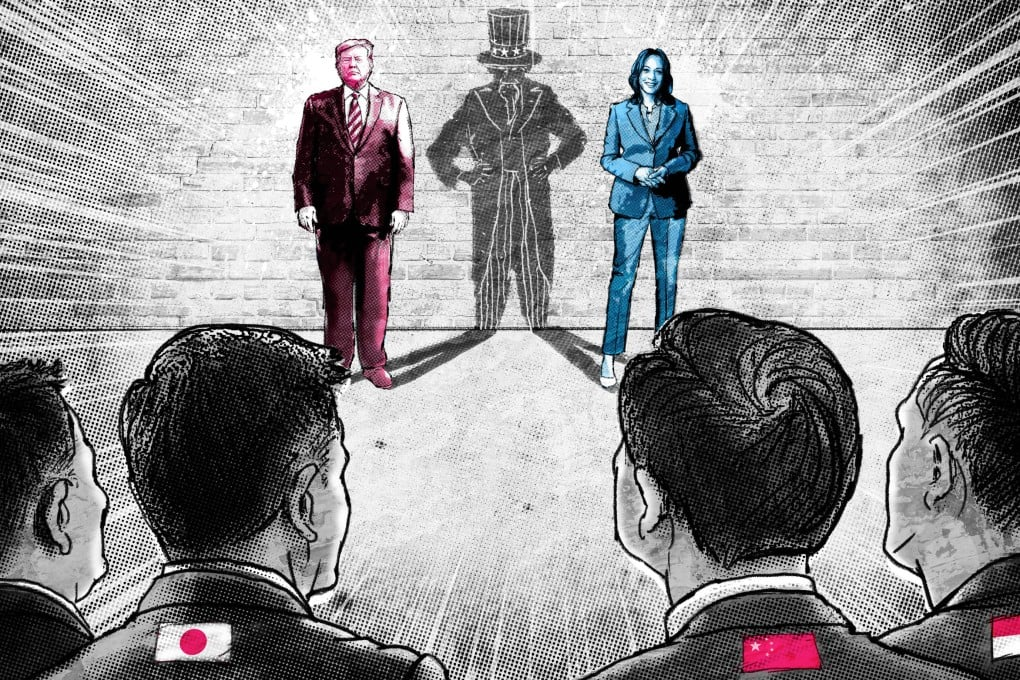

The Philippines is likely to maintain a “low-intensity” approach to China in the transition period after the United States election, a survey by a Beijing-based think tank has concluded.

The South China Sea Probing Initiative spoke to six analysts about how they expected the territorial dispute to unfold in the wake of Tuesday’s vote, including one who said a large-scale conflict was unlikely in the foreseeable future.

“During the transition period of the US government, the Philippines is likely to continue engaging China at sea in a low-intensity manner,” Ding Duo, an associate research fellow at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, said in the survey.

“On the legal front, the Philippine president might sign the Maritime Zones Act, using domestic legislation to legitimise gains acquired unlawfully and to expand its unilateral claims.”

The act would enshrine into domestic law the limits of the Philippines’ maritime claims, including its exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea.

He also said that in the long run Manila might push for talks with other South China Sea claimants about their maritime boundaries and leave Beijing out of the picture. He also warned that it could trigger a further round of international arbitration.

A 2016 tribunal in The Hague ruled that there is no legal basis for China’s expansive claims in the waters in a case brought by the Philippines. Beijing has rejected that ruling.

In June, Manila filed a submission to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, seeking to extend the legal limits of its continental seabed off the west coast of Palawan.

The two countries have clashed repeatedly in the South China Sea over the past year or so around disputed features such as Scarborough Shoal, Sabina Shoal and Second Thomas Shoal, where Philippine ships regularly try to carry out resupply missions to marines stationed on a grounded warship.

Manila has regularly accused Chinese ships of adopting aggressive tactics, including the use of water cannons and lasers and attacking and injuring personnel.

Hu Bo, the director of the South China Sea Probing Initiative, said he was “cautiously optimistic” about the situation, adding that some of the tensions had been overdramatised and there was no sign of a large-scale conflict.

“As the principal powers steering the region’s dynamics, China and the United States agree robustly on preventing conflict and maintaining peace, despite both preparing for the worst-case scenario,” Hu said.

“This policy stance has been clearly communicated through various bilateral channels, and it is expected to hold steady, independent of changes in the US presidency.”

But Ding said the US intended to “reshape the security environment around China” and could use the dispute to do so, along with strengthening its alliance with the Philippines.

Washington has a network of alliances across the Asia-Pacific region and has been building security partnerships with other countries, including other South China Sea claimants. China regards this as interference by the US and has repeatedly urged other countries to avoid outside influences.

China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations have been engaged in protracted talks about a code of conduct to reduce the risk of conflict in the South China Sea for the past two decades, and aim to finalise the code by 2026.Wu Shicun, founding president of China’s National Institute for South China Sea Studies, questioned how effective any code would be, and added that claimants were likely to take a range of actions to assert their claims.

“Even if the negotiating parties can reach a compromise to agree on a ‘simplified’ version of the rules, the code’s ability to effectively manage the crisis and restrain the actions of the parties involved in the South China Sea will remain limited,” he added.