Another element in the US Air Force’s plans for long-range operations, essential for Asia-Pacific deterrence, may have emerged from under cover of secrecy.

It looks like we’ve just got a good view of a shadowy uncrewed aircraft designed to fly far and slip into an enemy’s defended zone, undetected until it starts jamming radars. Quite likely, it would carry missiles to knock out radars.

Put another way, the evidence adds up to an electromagnetic attack aircraft—like the Boeing EA-18G Growler but highly stealthy and uncrewed. Northrop Grumman or, more likely, Boeing would seem to be the prime contractor. And the evidence suggests that the aircraft is not new: it was glimpsed a decade ago and was an active program in 2010, so either development has been in fits and starts or the type is operational.

Secret aircraft projects are dangerously fascinating, and excessive interest can get you on to CIA files. YouTuber Anders Otteson is one of the latest to follow the trail of the early 1990s Interceptors (a loose confederation of Area 51 observers). He bounces around the Mojave Desert in a comfortably equipped schoolie—a modified school bus, named Janet—with radio and a stack of cameras with low-light and infrared front ends.

Otteson just hit more pay dirt than most Mojave miners have done in decades, with an infrared video of an aircraft (10:00 mark) with a pure triangle shape. In the secret-aeroplane community, such things have long been dubbed mantas or doritos, the latter being a brand of triangular corn chip, and that’s the nickname given to the one that Otteson caught on video. ‘Dorito’ was also the nickname of the McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics A-12, which defense secretary Dick Cheney ruthlessly killed off in 1991.

Is the A-12’s ghost haunting the desert? This is not the three-sided phantom’s debut. Back in 2014, Steve Douglass (one of the original Interceptors) and Dean Muskett caught a flight of three aircraft of similar shape over Amarillo, Texas. A month later, another unidentified aircraft—which likewise did not resemble a Northrop Grumman B-2—was seen over Wichita, Kansas.

It was not at all clear at the time what purpose such an aircraft might serve, but one of the more satisfying aspects of the secret-aircraft hunt is when a piece of evidence in hand contains more data than you thought it had.

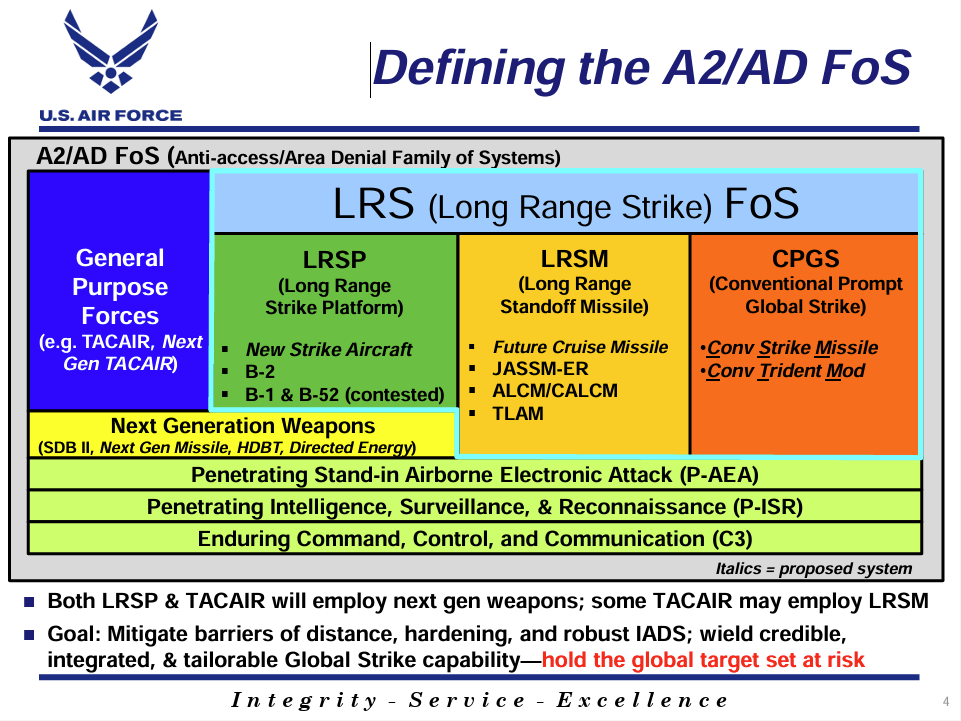

A briefing was delivered at a National Defense Industrial Association conference in 2010 by Major General Dave Scott, then the head of the US Air Force requirements shop. The good stuff is in slide 4.

In 2010, the USAF’s plans for investment in long-range strike were firming up. After its plans for an ultra-capable and expensive Next Generation Bomber had been cancelled in 2009, it reformulated its program as a Long-Range Strike Family of Systems (LRS-FoS) that would deliver the same capabilities at lower risk.

The key to slide 4 is at its lower right corner: ‘Italics = proposed system’. The document has been prepared in 2010, so the ‘New Strike Aircraft’ is still ‘proposed’. It soon became Long-Range Strike—Bomber (LRS-B) and eventually the Northrop Grumman B-21, now in full-scale development.

Other ‘proposed’ projects on slide 4 have also become reality. The Future Cruise Missile is Raytheon’s AGM-181 Long Range Stand Off Weapon, and the Conventional Strike Missile has materialised as two related projects—the Army Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon and the Navy Conventional Prompt Strike missile.

Three programs are listed in Roman type, signalling that they were active and funded in 2010. Penetrating Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (P-ISR) can now be confirmed as the Northrop Grumman RQ-180, which I reported on in 2013. Historian Peter Merlin’s 2024 history of Area 51, Dreamland, confirms the existence of the RQ-180 and that it first flew in 2010. Since then, an isolated facility has sprung into existence on the north side of Andersen Air Force Base on Guam, with its own rebuilt runway and two hangars. It’s probably for RQ-180s.

Another active project on Scott’s chart is Enduring Command, Control, and Communication (C3). This is now the $154 billion US nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) program.

The remaining active project on the chart is the one we’re interested in: Penetrating Stand-in Airborne Electronic Attack (P-AEA). It’s likely to be Anders Otteson’s Dorito.

Like the US Navy’s carrier-based Northrop Grumman X-47B technology demonstrator, it may well have been a fall-out from the Joint Unmanned Combat Air Systems (J-UCAS) program, which was terminated in early 2006. By that time, the competitors, the X-47B and Boeing X-45C, had each grown to maximum take-off weights around 20 tonnes, with 1,800 kg of internal load.

Northrop Grumman secured the subsequent navy demonstration contract, showed in 2013 that the X-47B could do carrier operations, and then spent several years trying to sell the navy on the type as a highly capable uncrewed combat aircraft.

The company did not succeed. The navy preferred the smaller and slower Boeing MQ-25 Stingray, optimised for tanking and intelligence and surveillance missions.

Meanwhile, it was disclosed in 2007 that Boeing’s secret-programs shop, the Phantom Works, had secured a contract for three X-45C technology demonstrators under J-UCAS, the first of which had been completed but hadn’t been funded for flight tests. In May 2009, Boeing announced that it would fly that aircraft using company funds, calling it the Phantom Ray. The aircraft performed one test flight in 2011—after which the program and demonstrator both vanished. Into a secret electromagnetic-attack program?

The absence of any visible Northrop Grumman push to sell an X-47-like aircraft to the USAF may be a further clue, in the sense of the dog in the night-time (one that should have barked but didn’t). Why would Northrop Grumman, particularly before it won the B-21 program in October 2015, not have promoted an X-47 derivative? One answer would be that the USAF had already made a choice.

And there was another possibly related development. The AGM-88G AARGM-ER anti-radar missile emerged quite suddenly in early 2015. It not only flies faster and farther than its predecessor, the HARM; it’s also designed for internal carriage. A highly stealthy electromagnetic-attack aircraft, such as a triangular one, would need to carry it internally.

Another silent hound: as the need for electromagnetic attack and suppression and destruction of air defense has been more widely accepted and is part of many air force plans, the USAF seems strangely content to leave the mission to the navy and its EA-18G Growlers.

The choice of a pure-triangle shape for the A-12, made 40 years ago, raised some eyebrows among observers of stealth technology. The straight trailing edge was seen as likely to generate a spike in radar reflections if the aircraft was directly nose-on to an emitter. But there’s a counter-argument if the mission is electromagnetic attack: the aircraft won’t point straight at the radar, because its primary weapons are long jamming arrays in its wing leading edges, producing narrow, high-power energy beams. To maximise the radio energy it pours into an enemy radar or communications receiver, it will keep one leading edge or the other nearly perpendicular to the target bearing.

And a triangular aeroplane has a lot of volume for fuel, helping with the great range that Western Pacific missions demand.

With the current US administration tightening its information policy, it may be a long time before anything official is said about the Dorito. But that’s why connecting the dots is important.