President Javier Milei’s openly critical stance toward China has evolved into an increasingly pragmatic collaboration.

The relationship between Argentina and China has undergone several ups and downs since Argentina’s President Javier Milei came to office and strongly distanced himself from Beijing.

What began as an openly critical stance toward the Asian giant has evolved, in a few months, into an increasingly pragmatic collaboration that reflects the complexities of the international scenario and the economic needs of Argentina, which prevail over ideological convictions. That said, changes in the Argentine Foreign Ministry, coupled with Donald Trump’s victory in the United States’ presidential election, once again cast a veil of mystery over the relationship between Argentina and China.

The first dramatic measure was Argentina’s decision not to join the BRICS group. The Argentine government formalized its decision to reject its invitation to join the bloc composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa shortly after taking office. This determination, previously telegraphed by the Foreign Ministry and Milei himself, was explained through a letter addressed to the leaders of each member country of the group.

Marcelo Suárez Salvia, Argentina’s ambassador to China, clarified to ReporteAsia that “it was not a rejection” of BRICS. Rather, he said. “the analysis of the foreign policy decisions of the outgoing government warranted an examination that needed to extend beyond the deadline for full membership.”

In so many words, the Milei government began with a negative stance strongly targeting China.

During the election campaign, candidate Milei had openly expressed his rejection of relations with countries that he considered contrary to his principles of economic freedom. In his speeches, China and Brazil were labeled as “communist regimes,” and he assured that his government would not pursue ties with them. There was, of course, a small practical problem: Brazil and China are Argentina’s two main trading partners.

This approach was maintained for a while in discourse, but reality began to prevail. At the G-20 meeting in Rio de Janeiro on November 18 and 19, Milei will no longer be able to avoid them: he will have to face both Brazil’s President Lula and China’s President Xi Jinping.

It will be Milei’s first official visit to Brazil after several disagreements with Lula, especially at the Mercosur summit in Paraguay where he chose not to participate in order to avoid a confrontation with the Brazilian president. Milei considers Lula’s Brazil to be hostile territory, politically speaking.

It’s important to clarify that Milei’s government should be analyzed from two perspectives. One is the discourse and the explosive nature of his statements: definitive, confrontational, aimed at creating noise and rupture. The other layer involves diplomatic actions, where the approach is much calmer and less confrontational.

In the case of Lula, for example, the discursive conflict and escalation are significant, but in commercial terms and on some political issues (such as the conflict at the Argentine embassy in Venezuela), both sides have shown a capacity for cooperation.

The same applies to China. The discourse has been openly confrontational, but diplomacy has lowered the tone and rearranged negotiations and conversations at various points.

For Patricio Giusto, executive director of the Sino-Argentine Observatory, “The main mistake of the Argentine government, which affected all foreign policy, was to deploy a diplomacy based on ideology, ignorance, and the personal preferences of the president.”

Giusto emphasizes that “there is a total misunderstanding of what China represents for Argentina and for the world in the president’s inner circle.”

The current situation places Milei in a position of more pragmatism and less ideology, especially in economic terms: there is an urgent need to strengthen Argentina’s international reserves. It was in this context that his administration decided to renew until 2026 the entirety of the activated currency swap for 35 billion RMB (equivalent to $5 billion), a financial agreement that had been in place since previous governments and gives Argentina an economic respite.

This renewal of the swap was one of the first gestures of openness toward China for Milei. It marked the beginning of a phase of rapprochement that, far from being an anomaly, seems to follow the pattern of other Latin American leaders like former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who criticized Xi during the campaign but within a few months in office was seen smiling in Beijing.

One of the first indications of a shift in Argentina’s foreign policy toward China occurred in June 2024, when Karina Milei, the president’s sister and one of his closest advisers, met with the Chinese ambassador in Buenos Aires, Wang Wei.

At that meeting, key issues for the future of the bilateral relationship were addressed, such as the rescheduling of the aforementioned currency swap and the possibility of increasing Chinese investments in strategic sectors such as lithium and agriculture.

Wang himself confirmed it in an interview with ReporteAsia: “In addition to trade, we hope to do more than exchanges for agro-industrial products, to go beyond cooperation in conventional areas, with more content of scientific and technological development and innovation, in sectors like new energies, digital economy, big data, artificial intelligence, as well as cultural and educational sectors.”

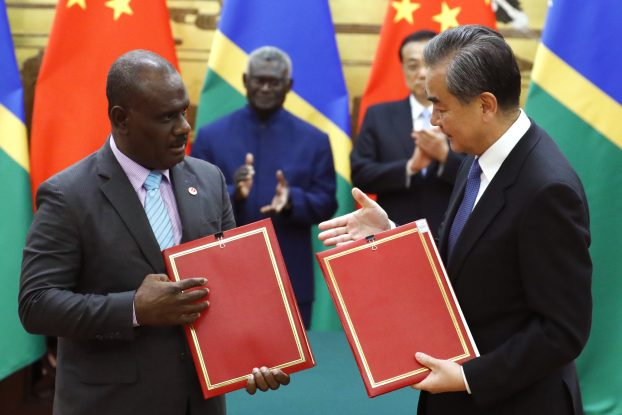

In September 2024, the highest-level meeting to date took place when then-Foreign Minister Diana Mondino met with her Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, during the United Nations General Assembly in New York. This meeting, which included the participation of key figures from the Argentine government such as Karina Milei and Minister of Economy Luis Caputo, was seen as a clear gesture of the intention of both countries to strengthen bilateral ties.

Eventually, Mondino was ousted from the government for voting against the United States’ blockade of Cuba at the United Nations, prompting fear that the hard-won progress might get stuck. Ideology, once again, was at play.

With Gerardo Werthein, the recent ambassador to Washington, as the new foreign minister, the foreign policy of the Argentine government is strongly tied to the United States-Israel axis and operationally very influenced by Karina Milei, whose credentials have nothing to do with managing these types of responsibilities. This raises even more questions about the future of the bilateral relationship with China.

According to Giusto, Werthein’s appointment “was a big surprise for China and cannot be said to be good news.” He continued, “After 10 complicated months, where it was very difficult to establish a normal diplomatic relationship, now it is like starting from zero with a new chancellor, who has no background in the relationship with China.”

Karina Milei was a key figure in the Argentina-China rapprochement. Not only was she the visible face in several diplomatic meetings with Chinese representatives, but she was also expected to visit Shanghai to participate in the China International Import Expo. This trip, which would have been the first official overseas visit for the president’s sister and would have reinforced the Argentine government’s intention to open new doors to economic cooperation with China, ultimately did not occur.

Another promise yet to be fulfilled came from the president himself. Before Mondino’s departure from the government, Milei gave an interview on one of Argentina’s most-watched TV programs where he announced that he would travel to China in January 2025 to participate in the summit of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC). This visit would be the first by the Argentine president to China, and a step on the path to consolidating relations between both countries. Of course, the meeting has not yet been officialized and nothing indicates that it will take place in January, before the Chinese New Year.

During that interview, Milei’s shift regarding the Asian country became clear when the president unabashedly stated that China “is a very interesting trade partner.” He concluded: “They demand nothing, only that they not be bothered.”

These dichotomies are what Milei’s government faces. With Trump in the White House, his government’s pro-China shift seems poised to be cut short. Even so, the country’s interests require straddling both sides of the international divide, and this is where diplomatic pragmatism plays its part.

In the words of Cortesi, “Argentina faces a new geopolitical reality with favorable economic parameters and a logistical outlet to Antarctica that makes it very attractive to both hegemonic powers. And this is Milei’s biggest bet.”

For Giusto, “The biggest challenge is to have a normal and mutually beneficial economic relationship, despite ideological preferences.”

So far, Milei has proven to be more practical than expected, both in his external relationships and his domestic policies. Will he break with this after Trump’s victory, or will he manage to also stay engaged with Xi Jinping? Undoubtedly, Argentina cannot afford to be at odds with either global power.