A fully independent Australian capability to make missiles remains a long way off, even with the US now showing greater support.

Australian–US cooperation on missile production was one of the few noteworthy areas of progress at last month’s annual AUSMIN meeting of the top Australian and US defence and foreign policy officials. Announcements there underscored that building up Australian industry to produce guided weapons and explosive ordnance, an effort known as the GWEO Enterprise, is no longer simply a national project; it has become an alliance initiative.

It’s clearer than ever that each stage of Australia’s crawl-walk-run approach to developing the GWEO Enterprise will hinge on US assistance, including technical knowledge, initial manufacturing support and, critically, access to global supply chains. Consequently, US defence industrial capacity shortfalls and lingering nervousness about information-sharing will likely shadow Australia’s efforts.

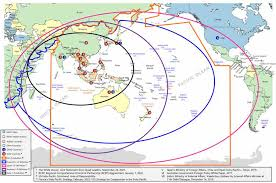

US policymakers have made plain the rationale for partnering with allies on munitions production. Conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East continue to deplete US stocks and strain production capacity for strike weapons and air-defence interceptors at a disquieting pace. Concerningly, war games run by leading US think tanks suggest that the US would exhaust stocks of key long-range missiles less than one week into a war to defend Taiwan.

In that context, progress on federated munitions production with Australia is welcome. At AUSMIN 2023, Washington agreed to transfer technical data to Australia to enable the co-assembly and eventual co-production of GMLRS truck-mounted missiles beginning in 2025. This year, the allies committed to additional cooperation on training rounds for PrSM short-range ballistic missiles and support for Australian manufacturing of solid-fuel rocket motors for these and other weapons. Along with the 22 August announcement of an $850 million partnership with Kongsberg Defence to build cruise missiles in Australia, the government is clearly moving GWEO from concept to a defence-industry reality.

Both Australia and the United States need this partnership to deliver. US officials have described efforts with Australia to build collective defence production capacity as a blueprint for similar initiatives with other partners. Yet Canberra must heed several lessons as it builds out its GWEO Enterprise with US co-production efforts at the centre.

First, greater sovereign production in Australia won’t eliminate dependence on the US. Self-reliance is not self-sufficiency. Acquisition of US-origin strike weapons will remain central to Australia’s missile mix even once local manufacturing for select missile components is underway. Though recent AUKUS-inspired export control reforms in the US may simplify defence technology trade between Australia and the US, lingering restrictions mean that many US missile-related datasets and components remain closely protected. As a result, even as Australia grows its production capacity, it’s likely that sovereignty over key parts, such as seeker heads and guidance systems, will remain elusive.

This means Australia will continue to rely in part on US production capacity, which will ultimately remain the pacesetter for a federated missile supply chain.

Recent setbacks in Japan’s efforts to boost production of Patriot air defence interceptors demonstrate the challenges to federated defence production. Despite Washington’s encouragement, Japanese efforts to manufacture and export greater numbers of Patriot rounds are capped by shortages of critical components produced exclusively by the US. This demonstrates that transitioning from walking to running will not simply be a matter of Australia doing more and doing it faster. Rather, progressing the GWEO Enterprise will equally depend upon the US getting its industrial house in order—and the degree to which it is willing and able to further empower Australia to help.

Beyond industrial capacity, Washington’s willingness to share sensitive information and technology with one of its most trusted partners will greatly influence the scope of the GWEO Enterprise. Sharing details about national supply-chain vulnerabilities is the greatest constraint on configuring allied inputs for maximum output. Yet, even within the trusted community of AUKUS, the US government is reticent about sharing information and technical data, despite Australia’s insistence that it seeks to complement, rather than compete with, US industry. This reluctance is a Cold War muscle memory that must be overcome for GWEO cooperation to achieve its potential.

The upcoming announcement of the Australian government’s strategic enterprise plan for sovereign missile manufacturing this year will provide overdue and welcome direction for the GWEO Enterprise. That GWEO has rocketed up the list of priorities at AUSMIN is also a strong show of intent. But even as Australia expands its missile production footprint, the policy community must be realistic about just how far sovereignty or self-reliance can go in the GWEO project.