Judging from the results of the annual Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore over the weekend, the United States’ strategy to prevent China from achieving hegemony in the Indo-Pacific region is making progress.

With American support assured, Philippines President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos — the keynote speaker — declared “Filipinos do not yield” to pressure from China. New initiatives were unveiled to deepen trilateral defense cooperation between the U.S., Japan, and South Korea. While to prevent inadvertent escalation in the Indo-Pacific, U.S.-China military dialogue reopened at the top level, after a two-year interlude.

But there is little room for complacency. There remain too many contradictions in U.S. Indo-Pacific policy. Left unresolved they may, over time, push friends toward neutrality and current and potential partners toward something worse. This risk is most salient when it comes to Indonesia.

To appreciate the importance of a nation few in the West understand or study, consider that earlier this year Prabowo Subianto, Indonesia’s current defense minister, won the country’s presidential election with over 96 million votes.

This electoral result alone should be reason for close links between the world’s second and third largest democracies — especially when China strives to convince the global south that Western-style democracy is at odds with their path to economic advancement.

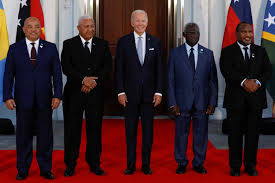

Still, simply holding elections does not make a country a U.S. ally. However, Indonesia is hardly on the fence when it comes to the international rules-based order. When current President Joko Widodo met Joe Biden in November 2023, their joint statement called on Russia to completely withdraw from the territory of Ukraine.

But Prabowo stated in his Shangri-La address that Indonesia’s stance on the Gaza conflict is predicated on adherence to that same international order. He warned of rising disillusionment among many global south countries, hinting at an overlooked but important truth: Indonesia’s principled foreign policy works in favor of U.S. interests in reinforcing a rules-based order in Asia.

To make the country a steadfast partner, there needs to be more give and take on the things Indonesians care about. Both Democrats and Republicans need to prioritize this: The Muslim-majority nation of nearly 300 million is projected to become the world’s fourth-largest economy by 2050. In the geopolitical contest for influence in Southeast Asia, Indonesia is the ultimate swing state.