Jennifer Kavanagh is a senior fellow and director of military analysis at Defense Priorities, a foreign policy think tank based in Washington.

Despite their distance from Ukraine’s battlefields, Japan and South Korea have been two of the country’s most generous supporters since Russia invaded in February 2022. Echoing Washington’s narrative about connections between security threats in Europe and Asia, leaders in both nations are betting that their military and economic commitments to Ukraine in the near term will serve as a down payment on security in the western Pacific over the long term.

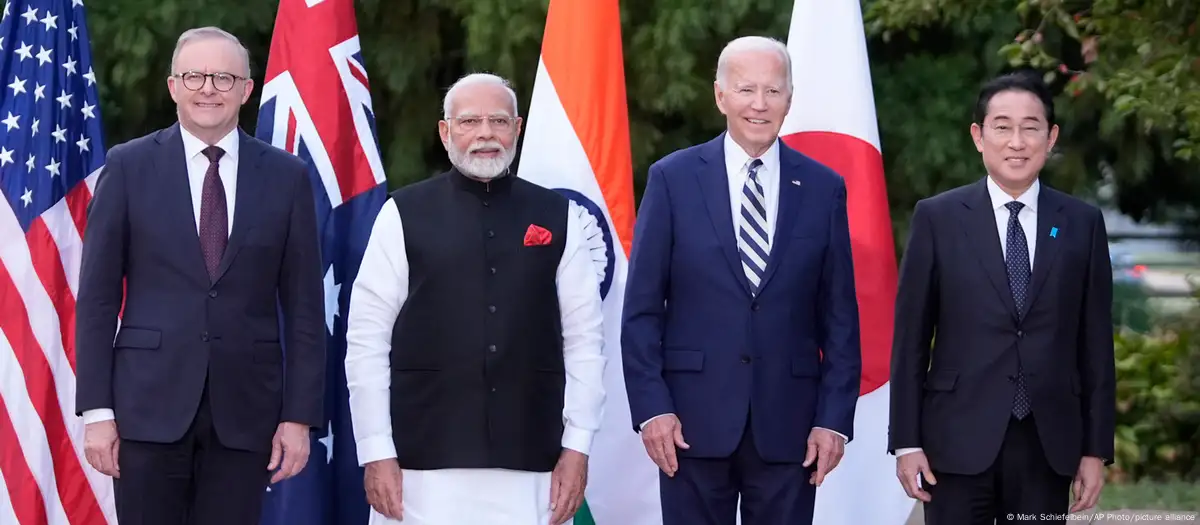

“The Ukraine of today may be the East Asia of tomorrow,” Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has said to explain his country’s support for Ukraine. South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol has similarly framed Seoul’s aid to Ukraine in terms of regional security, arguing that Russia’s growing military ties with North Korea pose “a distinct threat …to peace and security on the Korean Peninsula and in Europe.”

Rather than preventing conflict in East Asia, however, their continued aid to Ukraine leaves Japan and South Korea more vulnerable to military threats by absorbing resources both countries need to strengthen their own defenses. At the same time, it ties Tokyo and Seoul to Europe, exacerbating Chinese and North Korean fears of encirclement and the risk of military action. Instead of looking westward, Japan and South Korea can better guarantee their security and prevent war in their region by investing heavily in their own defenses and those of their regional partners, while limiting support to Ukraine to diplomatic backing.

For its part, Japan has committed as much as $12 billion in economic aid to Ukraine, making it one of Kyiv’s top donors. Japan has also provided drones and military vehicles, and has agreed to the indirect transfer of Japanese-built Patriot air defense missiles via the U.S.

South Korea has sent nonlethal military assistance such as bulletproof vests and mine detectors, and recently made a long-term $2.3 billion commitment to rebuild Ukraine’s defense sector. Like Japan, South Korea has provided indirect lethal military assistance through Washington, including 300,000 rounds of 155mm ammunition. Seoul has also allowed some of the military hardware it has sold to Europe to be passed on to Ukraine.

Both Kishida and Yoon have publicly justified their assistance to Ukraine as a commitment to upholding the rules-based international order, but they are also likely eager to prove themselves to be good allies and “global partners” of the U.S., and to build closer ties with Europe, in hopes of winning reciprocal aid if conflict arrives on Asia’s shores.

Regardless of its rationale, Tokyo’s and Seoul’s economic and military support to Ukraine is a mistake.

First, its main justification — the supposed linkages between the security threats in Europe and Asia — is largely imagined. There is no indication that a Russian triumph in Ukraine would accelerate a Chinese invasion of Taiwan or encourage North Korea to try its luck against Seoul, or that a Russian defeat fueled by donations from South Korea and Japan would dissuade either adversary from using military aggression. Because Ukraine is not a formal ally of the U.S., Japan, or South Korea, China and North Korea are also unlikely to draw conclusions about their resolve in Asia from their support — or lack of it — for Kyiv.

Second, Japan’s and South Korea’s significant commitments to Ukraine may weaken their own defense capabilities, absorbing resources that both countries need to address military vulnerabilities. For Japan, a weakening yen has eroded its much celebrated larger defense budget by as much as 30%, forcing it to delay military investments in munitions and air defense that are badly needed after decades of low defense spending. Japan should be devoting available funds — and Patriot missiles — toward its own defenses, rather than giving them away to Ukraine.

South Korea has more robust military capabilities than Japan, but also some substantial defense gaps. For example, it lacks the logistics capabilities and munitions stockpiles it would need for a protracted war and remains dependent on the U.S. for combat support capabilities. Seoul’s decision to donate 155mm ammunition to Ukraine’s war effort makes little sense in this context. If South Korea chooses to provide Ukraine more direct lethal military aid, Seoul’s tradeoffs between investing in its own defense resilience and supporting Ukraine will increase.

Finally, Japan’s and South Korea’s growing ties with Ukraine’s European supporters reinforce Chinese and North Korean concerns about what they perceive as a global U.S.-led security bloc aimed at containing their ambitions. Beijing and Pyongyang reacted negatively to the participation of Tokyo and Seoul in the recent NATO summit and its discussions about Ukraine. Beijing opposed even the attendance of its neighbors, warning Kishida beforehand not to damage “mutual trust” between their nations. By fueling Chinese and North Korean insecurities, Tokyo’s and Seoul’s growing commitment to Ukraine could worsen regional tensions and elevate the risk that one or both adversaries turn to military provocations.

Contrary to the assertions of leaders on both sides of the Pacific Ocean, the path to preventing conflict in East Asia does not run through Ukraine. The best way to avert war over Taiwan, on the Korean Peninsula, or in the South China Sea would be for Japan and South Korea invest heavily and quickly in their own defenses and those of their regional neighbors, turning much of Asia into hard-to-conquer unappealing targets for regional aggressors.

For Japan, this would mean redirecting money and military aid that would have gone to Ukraine to its own military forces, spending on defensive capabilities like naval mines and air defense, and hardening its military infrastructure. South Korea should similarly focus on deepening its defensive arsenal and developing combat support capabilities to withstand a long war. As an exporter of military equipment, South Korea might also work to stiffen the defenses of others in the region, for instance the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

Japan’s and South Korea’s willingness to aid Ukraine reveals them to be team players. But with threats in East Asia multiplying, now is the time for Tokyo and Seoul to put themselves first.